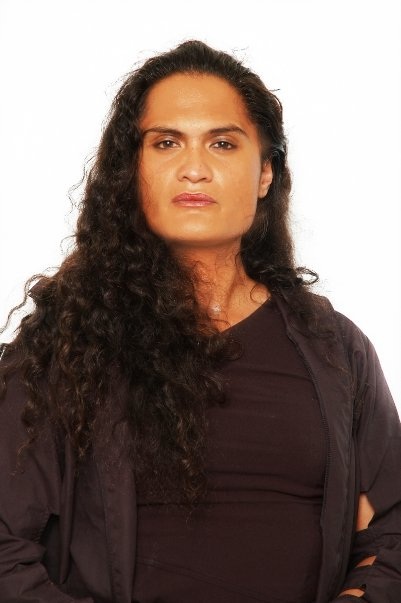

Transsexual Stacey ‘just another girl’

Hamilton woman Stacey Kerapa’s story pokes holes into the ideas many of us may have about transsexuality,

With thick, tousled black hair and a natural grace, Stacey Kerapa, 35, is a striking woman. The vibe she exudes is almost maternal, warm, and yet Stacey is ngaa Tane he ahua wahine. She was born into the body of a boy – the true embodiment of Simone de Beauvoir’s iconic statement that one is not born a woman, but rather becomes one. Her story is one which pokes holes into the ideas many of us may have about transsexuality, and the nature of our own strangled definitions of gender:

Mackenzie: Is there a difference between transvestite, transgender and transsexual?

Stacey: A transvestite is someone who dresses up in women’s clothing [or men’s if they are a woman] for sexual gratification.”Transsexual” was more so bestowed upon us when they were trying to work out “What’s this phenomenon going on in communities”? – and so they called us transsexual because we transcended the boundaries of the normal male/female role. We weren’t quite either. These days “transgendered” more applies to those who have had the actual sex-change operation.

M: So you are attracted to men?

S: Only.

M: At what point in your life did you realize you were meant to be Stacey?

S: I used to run around the lounge at a really young age with my mother’s petticoats wrapped up around my neck and pretend that I was Christie Brinkley [giggle], because Christie Brinkley was a black girl in my eyes! So it was probably around that time is when it first started – the actual realisation of it all, and putting it into practice…probably around the age of 13.

M: How did your whanau react to your realisation of who you were?

S: I actually have a gay brother and a lesbian sister. My brother is the oldest, and when he came out my parents really freaked out – they went to psychologists and they thought they had done something really terrible as parents. And then when my sister was about 15 or 16, she came out, and it was like “okay, there’s just something amiss here.” So by the time I came out they were sort of braced for the impact because they saw something was different. [My transsexuality] has never really been an issue for my parents, except that it took them nearly 20 years to stop with the Freudian slips, like saying “he, him, son”. Now, these days, my father is quite happy to call me his daughter, “her,” and “my darling”.

M: Do you think their reaction is typical of a lot of Maori families? Do you know?

S: I would estimate that around 90% of us get that kind of treatment because, as I understand it, there has always been a place for indifferently [gendered] children within Maoridom. So it didn’t matter if you were “camp” or whatnot, because your nannies would step in and take you, and there would always be a role. Although I do know of [Maori] families who have not embraced their children like I was lucky enough to be.

M: Do you feel that there’s much of a difference between being a Maori transsexual and non-Maori in terms of how you’re treated, both by whanau and by the general public?

S:I think definitely, here in New Zealand, you do have an advantage [if you are Maori]. I know a lot of non-Maori who have been totally disowned – thrown to the kerb and hoped that they’d just cease to exist. Yet even Pacific Islanders in New Zealand treat their trans whanau just the same as Maori would. Right up to Hawaii, all those that fall into the Pacific Triangle, we all have trans people in our communities and we all have a designated role for those people, and we’re absorbed by our hapu and our iwi.

M: What steps have you taken, physically, to become Stacey? Have you undergone surgery?

S: No, I’m a pre-operative transsexual. I’ve taken hormone therapies, grown breasts, and that also reduces the growth of facial hair, as well as your libido. So you don’t necessarily ‘react’ like a normal fella…even though at times during that practice, it can happen. It just has to be the right moment!

M: Aside from physical characteristics, what do you feel it takes to become a woman?

[pullquote] I suppose when we look at what “defines” men and women, we think of genitals. But for a lot of trannies, queens, whatever you want to call us, it’s more: “I feel pretty.” .[/pullquote]S: I suppose when we look at what “defines” men and women, we think of genitals. But for a lot of trannies, queens, whatever you want to call us, it’s more: “I feel pretty.” So you could go out and have the best hairdo, the best makeup, the best outfit, and still look like the bearded lady, but as long as you’re feeling beautiful, and that’s your perception of what it feels like to be woman, then [you’ve got it]. Unfortunately not a lot of the girls were blessed with good looks, and with some [transsexuals] it’s like “oh, my dear!” but you’ve still gotta give ’em that kudos, because, well, for lack of better words – they’ve got the balls to do that!

M: You lived in Auckland for 16 years – do you get a different public response now that you’re back in Hamilton?

S: Public response is very different in Hamilton. You can definitely tell when the university’s in and when it’s on holidays! I was lucky because I went to school [in Hamilton]. I went to Hillcrest High School and Church College of New Zealand. So I got to meet a lot of people [growing up], and through netball as well, and that gave me an in-door to a generation which is now a manager, or on City Council, or running Hamilton somehow. So my responses are different to a lot of the younger [transsexuals], because a lot of the younger ones actually force it out there that “I’m woman,” and they strut around with their hooker outfits in broad daylight and everyone’s staring…for the wrong reasons. I’m more of a mingle and blend kind of person – so unless you’re looking, you’re not going to know. You just walk on by and I’m just another girl. That’s how I like it.

M: What is the general response from uni students?

S: With uni students it’s pretty cool. Nine times out of ten it’s more inquisitive, rather than rude or intrusive. I’m also ex-Waikato Uni, so I know my way around a bit.

M: What did you study?

S: I did Maori and Pacific development, with a double major in psychology, and then I took off to get a life! I went to Melbourne, and then I went to Auckland, and then I went to all these other places and I’ve just left it sitting there. Now, I’m just about to finish my last degree, which is social work and community development. I just need a placement and a research paper to complete, and then I’m done!

M: What been the hardest part about being Stacey?

S: I suppose the most difficult part is watching the younger generation actually go through a phase I conquered a long time ago – and that is understanding that not everyone understands us! I think that’s not only important for communities, but also if you are a parent of a trans person. Your acceptance [of your child] is actually a given as a parent, because you are going to accept your child even if you don’t have a bloody clue what they’re on about… but it’s actually about understanding your child. Don’t just accept them because they’re gay, trans, or whatever – actually try to understand them.

M: What ideas around transsexuality need to change in New Zealand, if any?

S: I think just normal courtesies and basic rights. If I want to be considered a female, I shouldn’t have to turn up with a doctor’s signature to say that I’ve undergone surgery. If I’ve been practising this lifestyle for so many years that it’s the dominant – the social – norm in my life, then that should be considered okay. But there are so many boundaries. It’s only been recently, since the To Be Who I Am report was released by the Human Rights Commission [2008] that we’ve actually had certain liberties given. We weren’t part of the Gay Rights bill. It was only applicable to gay men and lesbian women. So once that went through, trans men and women had no rights because you were neither a “man” or a “woman,” nor were you “gay” or “lesbian.”

M: Since you mentioned that you’re studying social work, is that where you feel you are headed?

S: Yes. All my life I’ve been around some sort of social work. My parents were foster parents for 21 years. So that kind of practice is normal to me – I can walk into some very volatile situations and come out with a really good social practice outcome. Also the fact that there aren’t many trans, or openly gay or lesbian social workers who can deal with these kids. Why on earth, for example, would I send a child in the system to a person who is perhaps, and I hate to use this term, a religious fanatic, and who’s also a social worker? You’re going to fill that kid’s head with what?

M: You’ve know who you were from a very young age, but can you remember what it felt like during that stage of realisation?

S: It was very scary. I knew what I was doing. I knew what I wanted and I knew where I wanted to go. It was more of a “how the hell am I going to achieve this?” “How am I going to face the world without being totally ripped to shreds?” Once you turn this way, nine times out of ten you go into prostitution. That’s something you’ll find about the community – we’re highly sexual, and that’s the usual line of work. [pullquote]I might come with all the best qualifications, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll get the job, based on the fact that I am a trans person. So that’s one of the harder things to get past when living this life. It’s not an easy life to live.[/pullquote]Say a queen turns up for a regular job – the first reaction you’ll get is, “Okay, I’ll just get the manager…” I might come with all the best qualifications, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll get the job, based on the fact that I am a trans person. So that’s one of the harder things to get past when living this life. It’s not an easy life to live.

M: If you had a young person in front of you now who was going through the experience you went through, what advice would you give them?

It would take a lot of talking to this person to actually understand them before I give them any advice…because it could just be a phase. My first set of questions would be based around “Is this really the life you want?” Because here we go…this is what happens, and if you’re not ready for it, it’s going to change you, but not in the ways that you want.